Why in News?

Recently, the Madras High Court, in S. Harish vs Inspector of Police, quashed the judicial proceedings and held that downloading child pornography was not an offence under Section 67B of the Information Technology (IT) Act, 2000. The High Court categorically said that watching child pornography per se was not an offence as the accused had merely downloaded it onto his electronic gadget and had watched it in private.

Key Highlights

- High Court referred to a case decided by the Kerala High Court where it had been held that watching pornography in private space was not an offence under Section 292 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC).

- This case related to the quashing a criminal case registered against a youth in 2016 by the Aluva police as he had been watching pornographic material on his mobile phone on the roadside at night.

- In this case, after investigation, the police had filed the final report and cognisance had been taken by the High Court under Section 14(1) of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012 and Section 67B of the IT Act.

- Section 67B(b) of the IT Act says that ‘whoever, – creates text or digital images, collects, seeks, browses, downloads, advertises, promotes, exchanges or distributes material in any electronic form depicting children in obscene or indecent or sexually explicit manner’ shall be punished on first conviction with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to five years and with fine which may extend to ten lakh rupees….’

- It is undisputed that two files pertaining to child pornography were downloaded and available on the mobile phone of the accused. The forensic science report also corroborated the presence of the two files.

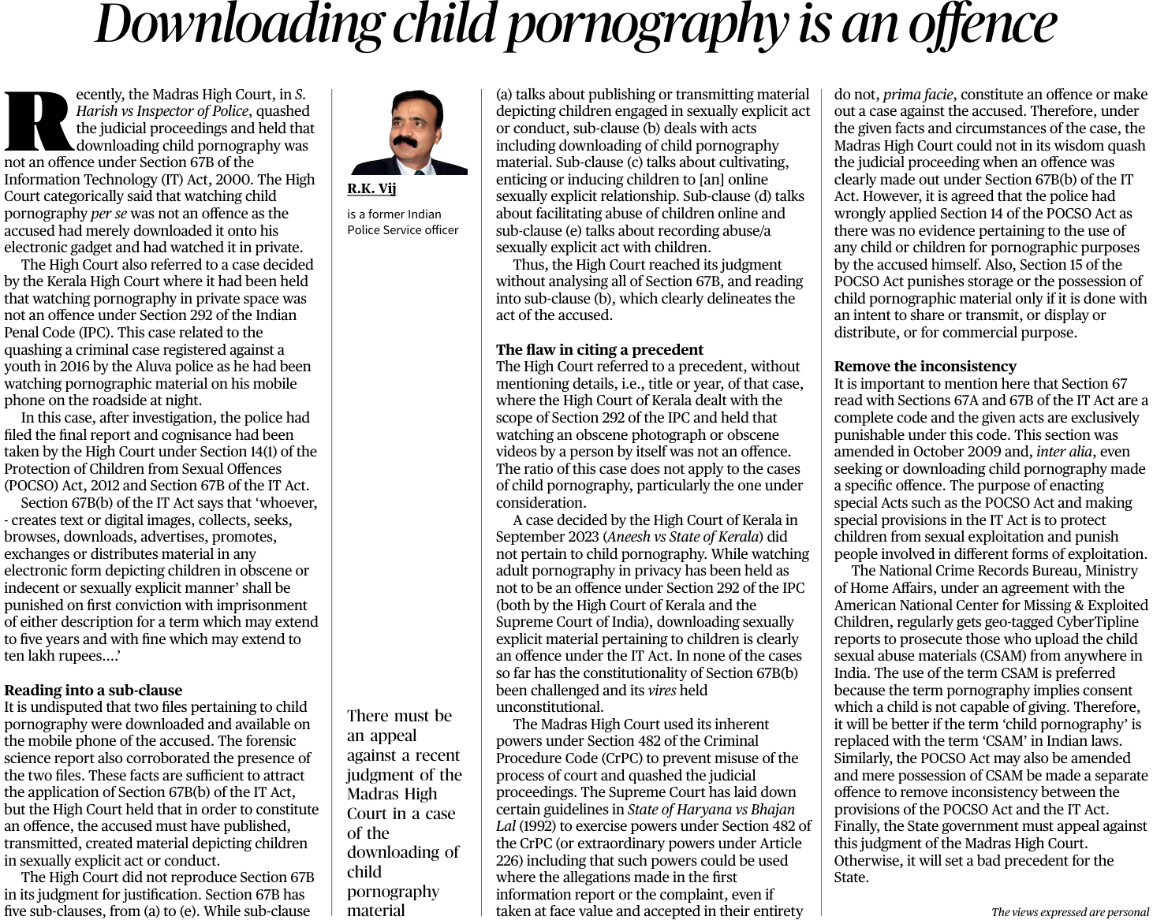

- These facts are sufficient to attract the application of Section 67B(b) of the IT Act, but the High Court held that in order to constitute an offence, the accused must have published, transmitted, created material depicting children in sexually explicit act or conduct.

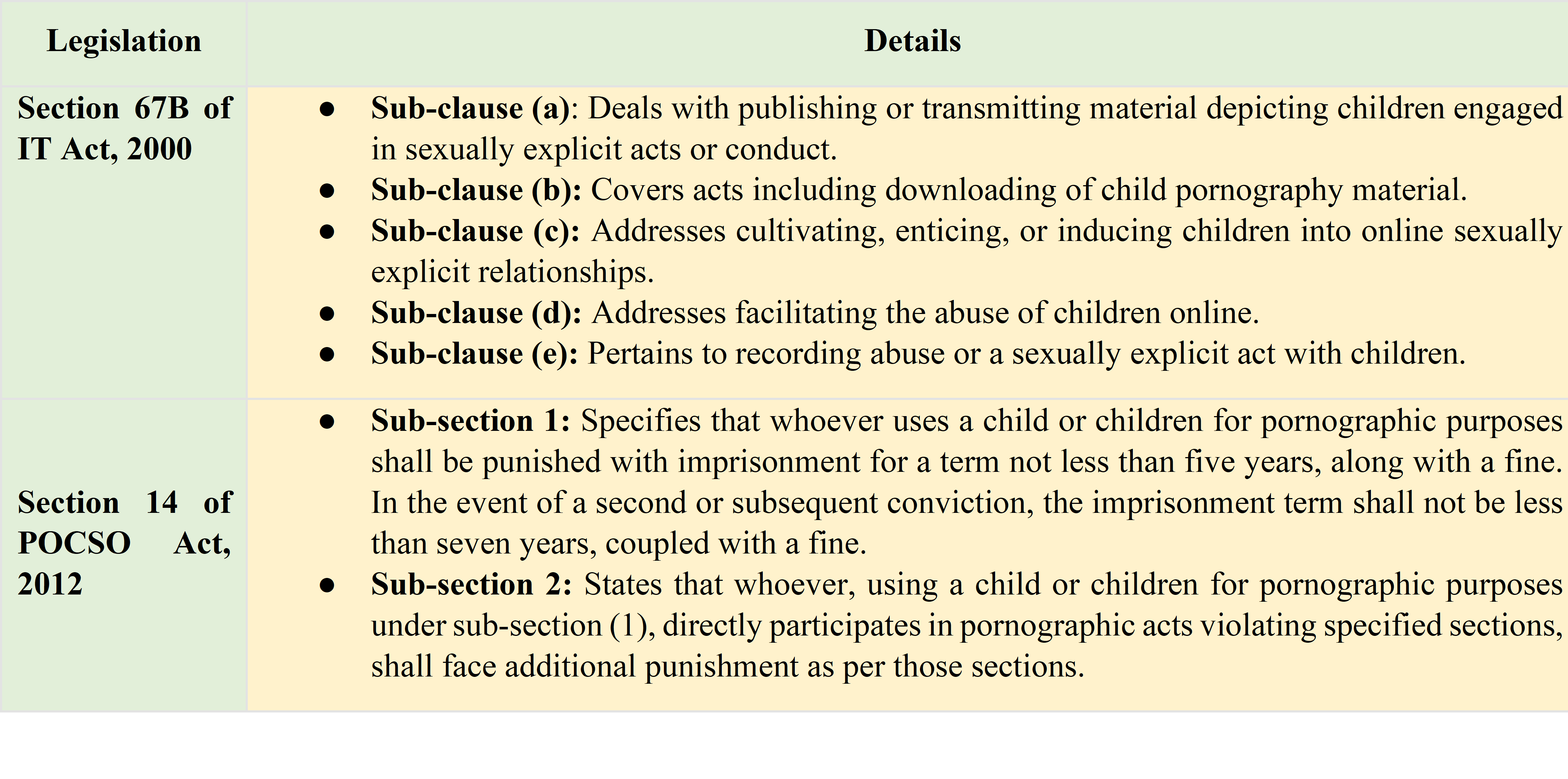

- The High Court did not reproduce Section 67B in its judgment for justification. Section 67B has five sub-clauses, from (a) to (e). While sub-clause (a) talks about publishing or transmitting material depicting children engaged in sexually explicit act or conduct, sub-clause (b) deals with acts including downloading of child pornography material. Sub-clause (c) talks about cultivating, enticing or inducing children to [an] online sexually explicit relationship. Sub-clause (d) talks about facilitating abuse of children online and sub-clause (e) talks about recording abuse/a sexually explicit act with children.

- Thus, the High Court reached its judgment without analysing all of Section 67B, and reading into sub-clause (b), which clearly delineates the act of the accused.

- The High Court referred to a precedent, without mentioning details, i.e., title or year, of that case, where the High Court of Kerala dealt with the scope of Section 292 of the IPC and held that watching an obscene photograph or obscene videos by a person by itself was not an offence. The ratio of this case does not apply to the cases of child pornography, particularly the one under consideration.

- A case decided by the High Court of Kerala in September 2023 (Aneesh vs State of Kerala) did not pertain to child pornography. While watching adult pornography in privacy has been held as not to be an offence under Section 292 of the IPC (both by the High Court of Kerala and the Supreme Court of India), downloading sexually explicit material pertaining to children is clearly an offence under the IT Act. In none of the cases so far has the constitutionality of Section 67B(b) been challenged and its vires held unconstitutional.

- The Madras High Court used its inherent powers under Section 482 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) to prevent misuse of the process of court and quashed the judicial proceedings.

- The Supreme Court has laid down certain guidelines in State of Haryana vs Bhajan Lal (1992) to exercise powers under Section 482 of the CrPC (or extraordinary powers under Article 226) including that such powers could be used where the allegations made in the first information report or the complaint, even if taken at face value and accepted in their entirety do not, prima facie, constitute an offence or make out a case against the accused.

- Therefore, under the given facts and circumstances of the case, the Madras High Court could not in its wisdom quash the judicial proceeding when an offence was clearly made out under Section 67B(b) of the IT Act.

- However, it is agreed that the police had wrongly applied Section 14 of the POCSO Act as there was no evidence pertaining to the use of any child or children for pornographic purposes by the accused himself. Also, Section 15 of the POCSO Act punishes storage or the possession of child pornographic material only if it is done with an intent to share or transmit, or display or distribute, or for commercial purpose.

- It is important to mention here that Section 67 read with Sections 67A and 67B of the IT Act are a complete code and the given acts are exclusively punishable under this code.

- This section was amended in October 2009 and, inter alia, even seeking or downloading child pornography made a specific offence.

- The purpose of enacting special Acts such as the POCSO Act and making special provisions in the IT Act is to protect children from sexual exploitation and punish people involved in different forms of exploitation.

- The National Crime Records Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs, under an agreement with the American National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, regularly gets geo-tagged CyberTipline reports to prosecute those who upload the child sexual abuse materials (CSAM) from anywhere in India.

- The use of the term CSAM is preferred because the term pornography implies consent which a child is not capable of giving.

- Therefore, it will be better if the term ‘child pornography’ is replaced with the term ‘CSAM’ in Indian laws. Similarly, the POCSO Act may also be amended and mere possession of CSAM be made a separate offence to remove inconsistency between the provisions of the POCSO Act and the IT Act.

- Finally, the State government must appeal against this judgment of the Madras High Court. Otherwise, it will set a bad precedent for the State.

Issues in Madras High Court’s Recent Judgement

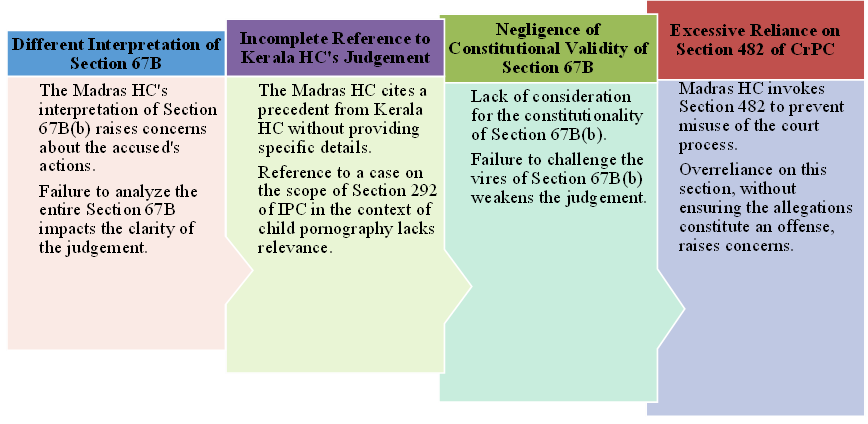

What is Child Pornography?

Child pornography involves the creation, distribution, or possession of sexually explicit material featuring minors.

It is considered a heinous crime with severe implications, contributing to the sexual exploitation and abuse of children.

Indian Scenario

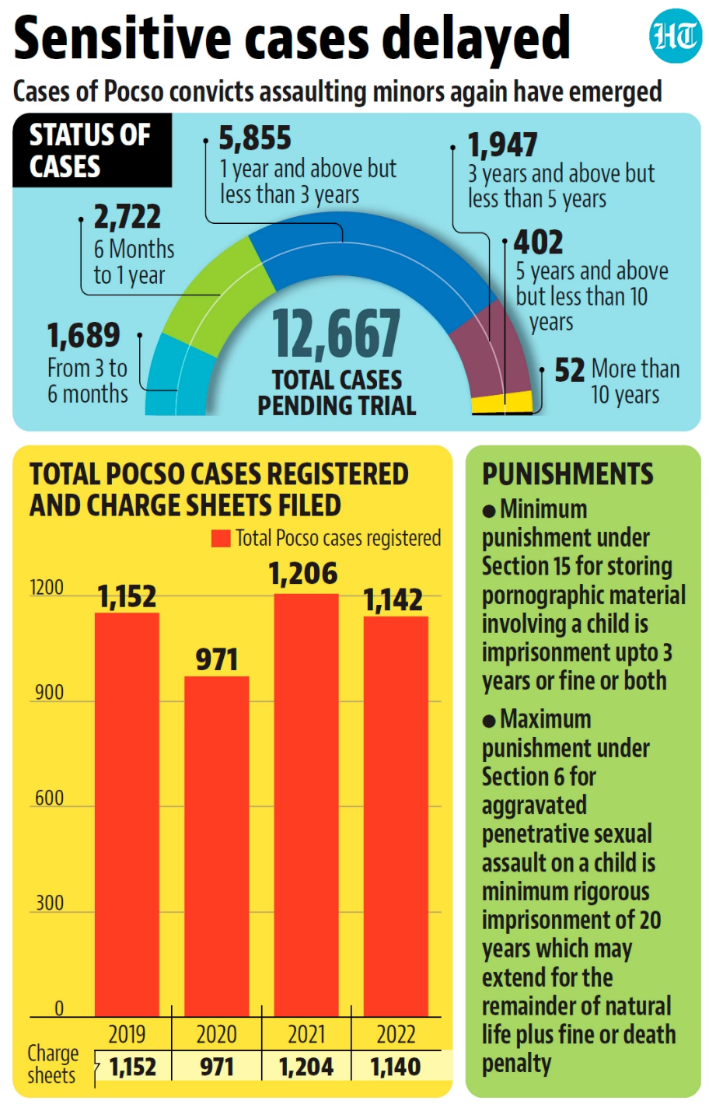

The spike in child pornography cases mirrors the alarming prevalence of online child sexual abuse in India. According to the NCRB (National Crime Report Bureau) 2021, cases have risen from 738 in 2020 to 969 in 2021.

Online Child Pornography

- Digital exploitation of minors through the production, distribution, or possession of sexually explicit material on digital platforms.

- The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act, 2019, defines it as any visual depiction of

sexually explicit conduct involving a child, including photographs, videos, or digitally generated images indistinguishable from an actual child.

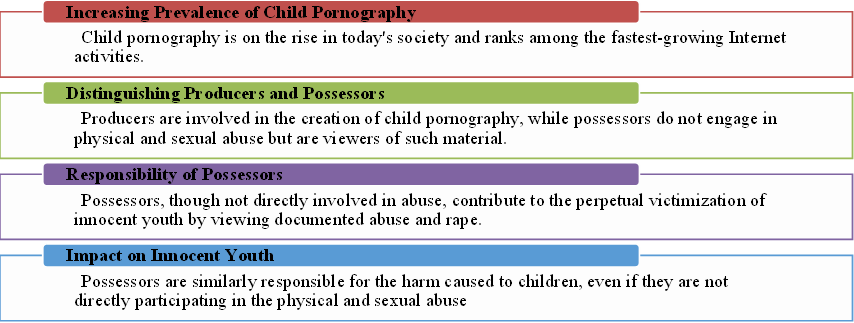

Impact of Child Pornography

- Psychological Impact: Pornography has a profound psychological impact on children, contributing to feelings of depression, anger, and anxiety.

- It can lead to mental distress, affecting various aspects of a child’s life, including their biological clock, work, and social relationships.

- Impact on Sexuality: Regular exposure to pornography creates a sense of sexual gratification and obsession, potentially influencing a willingness to replicate such behaviors in real life.

- Sexual Addiction: Some experts liken pornography to addiction, as it can produce similar effects on the brain comparable to the regular consumption of drugs or alcohol.

- Behavioral Impact: Adolescent pornography use is linked to stronger beliefs in gender stereotypes, particularly among males.

- Male adolescents who frequently view pornography are more likely to perceive women as sex objects, influencing their attitudes and behaviors.

- Supportive Attitudes to Violence: Pornography may strengthen attitudes supportive of sexual violence and violence against women, contributing to a concerning societal impact.

Challenges to Deal with Pornography

- Challenges in Addressing Pornography: The impact of pornography varies between children from different socioeconomic classes, necessitating diverse approaches for effective intervention.

- Cultural Context in India: In India, sex is often viewed negatively, creating a lack of healthy family discussions on the subject. This absence leads children to seek information externally, often resulting in the development of a pornography addiction.

- Difficulty in Detection: Agencies face significant challenges in detecting and effectively monitoring child pornography activities.

- Ubiquity of Obscene Content: The widespread availability of explicit content on mainstream websites and OTT services like Amazon Prime, Netflix, Hotstar, etc., complicates the differentiation between non-vulgar and vulgar content, posing a challenge for effective regulation.

Legislations related to Child Pornography in India

What is the POCSO Act?

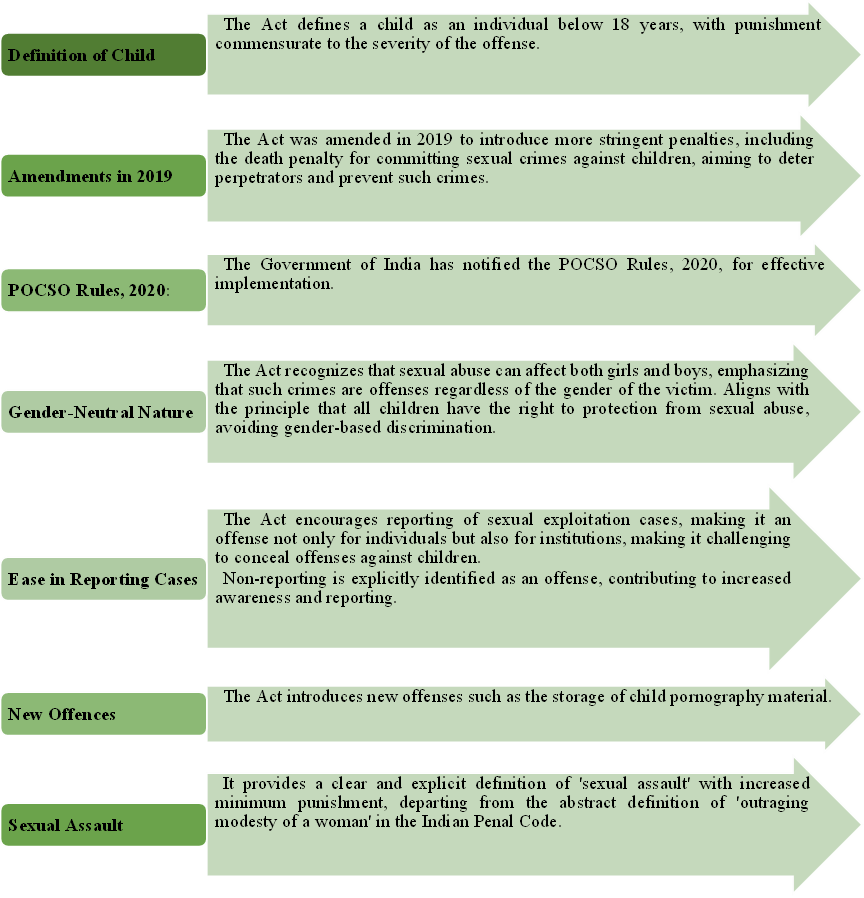

- The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act became effective on 14th November 2012, in alignment with India’s ratification of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1992.

- The primary objective is to address sexual exploitation and abuse of children, offering precise definitions and appropriate penalties for offenses that were either undefined or insufficiently penalized.

- Enacted with the primary objective of safeguarding children from sexual assault, harassment, and pornography, the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 prioritizes the best interests and welfare of children throughout its provisions. The Act defines a child as an individual below eighteen years, emphasizing the paramount importance of ensuring the child’s healthy physical, emotional, intellectual, and social development at every stage.

- This legislation encompasses various forms of sexual abuse, distinguishing between penetrative and non-penetrative assault, sexual harassment, and pornography. In specific circumstances, such as when the abused child is mentally ill or when the perpetrator holds a position of trust or authority, like a family member, police officer, teacher, or doctor, the Act categorizes sexual assault as “aggravated.”

- The Act assigns a crucial role to the police as child protectors during the investigative process. It mandates the prompt disposal of child sexual abuse cases within one year from the date of reporting the offense. In an effort to enhance its effectiveness, the Act underwent amendments in August 2019, introducing more severe punishments, including the death penalty, for individuals found guilty of sexual crimes against children.

Key Features

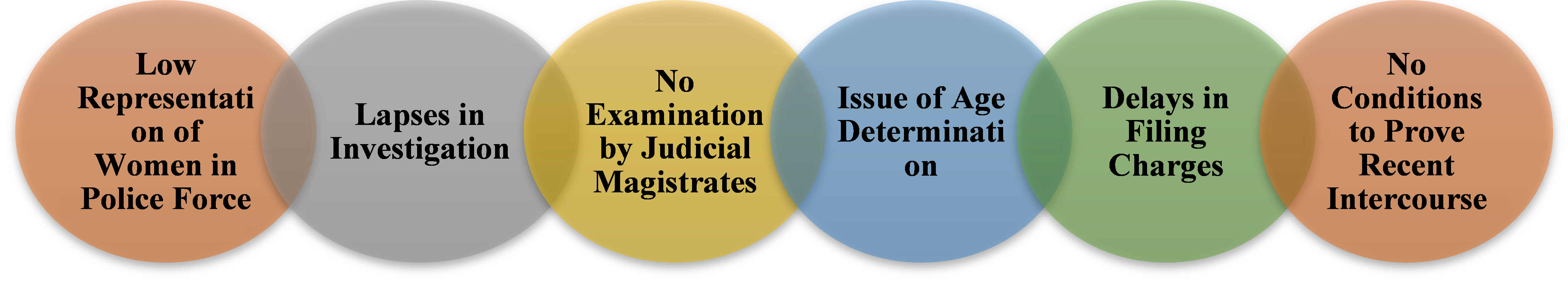

Issues and Challenges with the POCSO Act

- Low Representation of Women in Police Force: The Act requires the statement of the affected child to be recorded by a woman sub-inspector, but with only 10% representation of women in the police force, and many stations lacking women staff, compliance is challenging.

- Lapses in Investigation: While there is a provision for recording statements using audio-video means, reports indicate lapses in investigation and crime scene preservation, as highlighted in the Shafhi Mohammad vs The State of Himachal Pradesh (2018) case.

- No Examination by Judicial Magistrates: Although the Act mandates recording the prosecutrix’s statement by a judicial magistrate, they are not called for cross-examination during trial, undermining the credibility of these statements.

- Issue of Age Determination: The Act lacks a provision for age determination for juvenile victims, relying on school records. The Jarnail Singh vs State of Haryana (2013) case emphasized using statutory provisions for age determination.

- Delays in Filing Charges: Despite the Act’s stipulation for completing investigations within a month, practical challenges such as resource shortages, forensic delays, or case complexity often lead to extended investigation periods.

- No Conditions to Prove Recent Intercourse: The Act does not impose conditions on the prosecution to prove recent intercourse, contrary to the Indian Evidence Act. This absence may hinder achieving an expected increase in the conviction rate, as observed during trials.

Way Forward

-

- Adherence to Existing Legislation: Sections 67B of the IT Act, in conjunction with related sections such as 67, 67A, and Section 14 of the POCSO Act, 2012, forms a comprehensive legislative framework targeting offenses related to child pornography. Specific provisions demonstrate the commitment to combating the sexual exploitation of children in cyberspace.

- Collaboration with NCRB: The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), Ministry of Home Affairs, collaborates with the American National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, receiving geo-tagged CyberTipline reports to prosecute individuals uploading child sexual abuse materials (CSAM) anywhere in India. This process should prioritize safeguarding the privacy and bodily integrity of child victims, avoiding open publication on websites.

- Shift to “Child Sexual Abuse Materials” (CSAM): Advocates recommend replacing “child pornography” with “child sexual abuse materials” (CSAM) to accurately convey the non-consensual nature of the content. This linguistic adjustment aims to enhance legal clarity and underscore the gravity of the offense.

- Consistency in Legislation: There is a demand to harmonize provisions between the POCSO Act, 2012, and the IT Act, 2000 to ensure uniformity in addressing offenses related to child sexual exploitation. Aligning these acts would streamline legal procedures, reinforcing the protection of children.

- Amendments to the POCSO Act: Proposed amendments to the POCSO Act may be necessary to categorize the possession of CSAM as a distinct offense, aligning it with the provisions of the IT Act, 2000. Such changes would rectify inconsistencies and provide clearer legal guidance in prosecuting perpetrators.

- Appeal against Madras High Court Decision: It is imperative for state governments and relevant investigating agencies to appeal against the Madras High Court’s decision to prevent setting a detrimental precedent. Upholding the integrity of laws related to child protection is crucial for safeguarding vulnerable populations and ensuring justice.

MPSC राज्य सेवा – 2025

MPSC राज्य सेवा – 2025