Why in News?

Anonymous donations of high value tend to undermine electoral democracy and governance as they facilitate a quid pro quo culture involving donors and beneficiaries. In striking down the Electoral Bond Scheme (EBS) under which anyone could buy electoral bonds and donate them to political parties for encashment, the Supreme Court of India has recognised this malaise and struck a blow for democracy and transparency in political funding.

Key Highlights

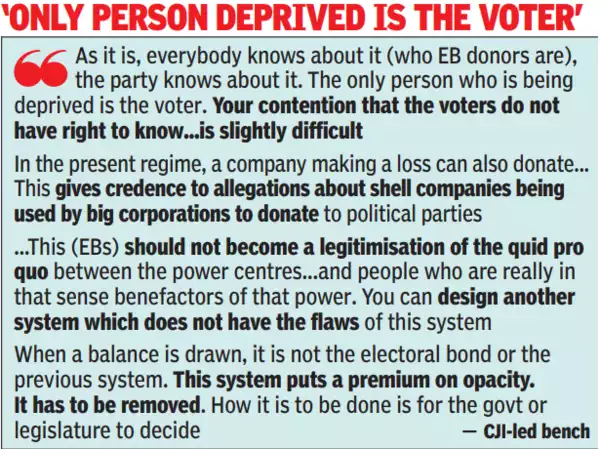

- The Court found that the entire scheme violates the Constitution, especially the voters’ right to information.

- It further found manifestly arbitrary, the amendment to the Companies Act that removed the cap of 7.5% of a company’s profit that can be donated to political parties without any requirement to disclose details of the recipient parties in its profit and loss accounts.

- It has also mandated disclosure of donation details since 2019.

- The judgment is one more in a long line of verdicts the Court has handed down to promote voter rights and preserve the purity of elections.

- Its earlier interventions led to the featuring of the ‘None of the Above’ option on the ballot, the removal of the protection given to legislators from immediate disqualification on conviction for a criminal offence, the mandatory disclosure of the assets and criminal antecedents of candidates in their election affidavits and expedited trials for MPs and MLAs involved in criminal offences.

- The Court’s reasoning is unexceptionable. It found that the primary justification for the EBS — curbing the use of ‘black money’ for political or electoral funding by allowing donations through banking channels — failed the test of proportionality, as it was not the least restrictive measure to abridge the voters’ right to know.

- It has made the logical connection between unidentified corporate donations and the likelihood of policy decisions being tailored to suit the donors.

- The judgment is a natural follow-up to a principle it had laid down years ago that the voters’ freedom of expression under Article 19(1)(a) will be incomplete without access to information on a candidate’s background.

- The principle has now been extended to removing the veil on corporate donors who may have been funding ruling parties in exchange for favours.

- While the verdict may help ease the hold that donors may have on governance through money power, a question that arises is whether the validity of the scheme could have been decided earlier or the issuance of bonds on a regular basis stayed.

What are Electoral Bonds (EBs)?

Nature of Electoral Bonds

- Interest-free bearer bonds or money instruments.

- Purchased by companies and individuals in India from authorized State Bank of India (SBI) branches.

Payment Similar to Bank Notes

- Similar to bank notes, payable to the bearer on demand.

- Devoid of interest.

Denominations and Purchase

- Sold in multiples of Rs 1,000, Rs 10,000, Rs 1 lakh, Rs 10 lakh, and Rs 1 crore.

- Can be purchased through a KYC-compliant account for making political party donations.

Validity and Anonymity

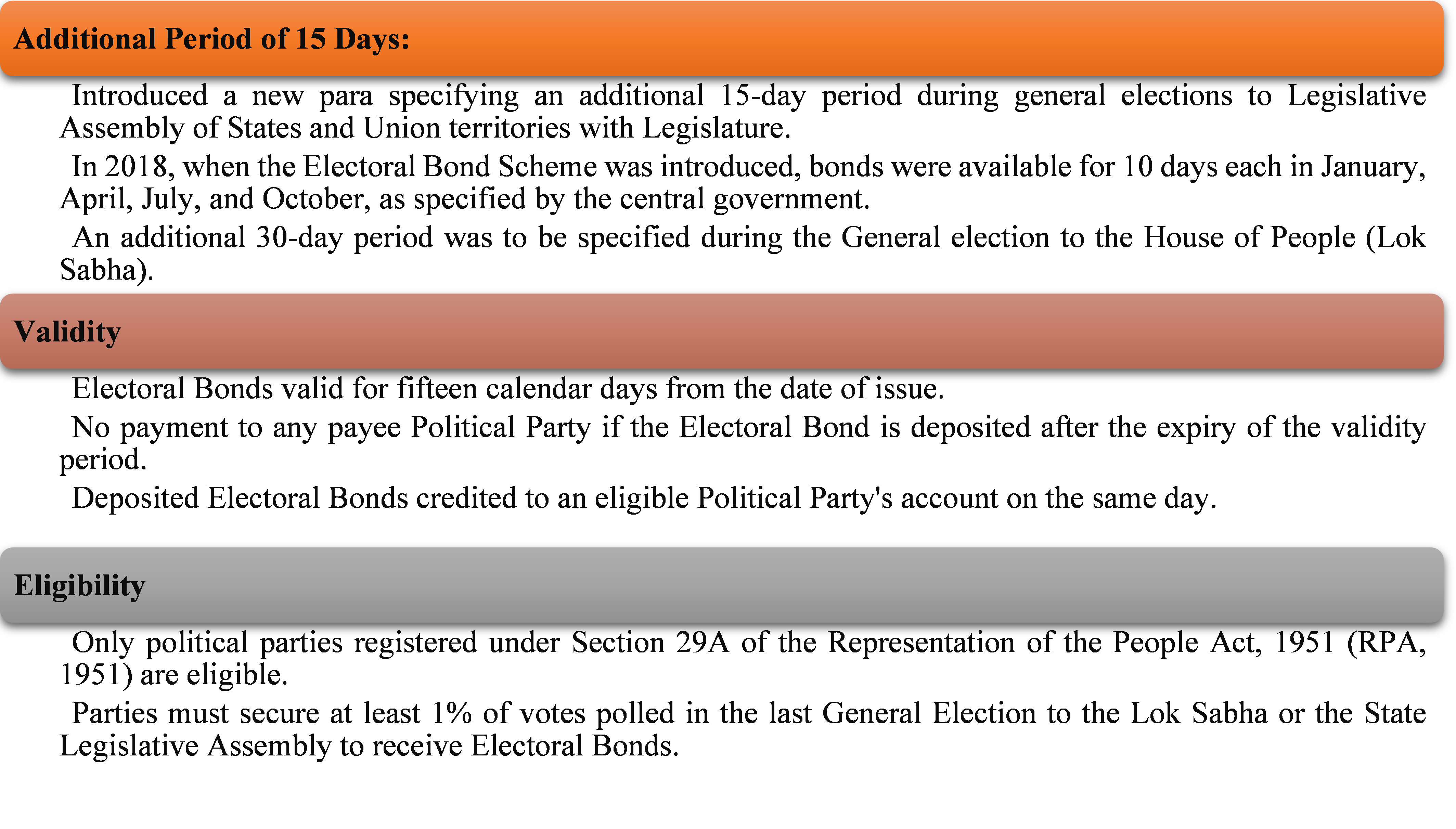

- Have a lifespan of only 15 days for making political donations.

- Anonymous as the name and donor information are not recorded on the instrument.

No Purchase Limit: No cap on the number of electoral bonds an individual or company can acquire.

Tax Exemption: Considered tax-exempt under Sections 80 GG and 80 GGB of the Income Tax Act for electoral bond donations.

Eligibility to Receive Funding

- Only political parties registered under Section 29A of the Representation of the People Act, 1951.

- Parties must secure not less than 1% of votes polled in the last general election to the House of the People or the Legislative Assembly of the State.

Encashment and Disclosure

- Political parties must encash bonds within a stipulated time.

- Eligible political parties can encash through a designated bank account.

- Disclosure of the amount to the Election Commission is mandatory.

Electoral Bond Scheme

Introduced by former Finance Minister Arun Jaitley in the 2017 budget session. Framed as an initiative to cleanse the political funding system and enhance transparency in political donations.

Launch and Legislative Amendments

- Launched through a notification on January 2, 2018.

- Amendments made to four legislations—the Representation of the People Act, 1951, the Companies Act, 2013, the Income Tax Act, 1961, and the Foreign Contributions Regulation Act, 2010 (FCRA)—via Finance Acts of 2016 and 2017.

Pre-existing Regulations

- Before the scheme, political parties had to disclose all donations above ₹20,000 publicly.

- Corporate companies were restricted from making donations exceeding 10% of their total revenue.

Eligibility and Allotment

- Every political party under Section 29A of the RP Act, securing at least 1% of votes in recent Lok Sabha or State elections, allotted a verified account by the Election Commission of India (ECI).

- Bond amounts must be deposited within 15 days of issuance.

Encashment and Unclaimed Bonds

- If a party fails to encash bonds within 15 days, the SBI deposits them into the Prime Minister’s Relief Fund.

- Bonds available for purchase for ten days at the start of each quarter and an additional 30-day period during Lok Sabha election years.

Donation Statistics

- According to an analysis by the Association of Democratic Reforms (ADR), between 2016-17 and 2021-22.

- Seven national and 24 regional parties received ₹9,188.35 crore from electoral bonds.

- BJP’s share was ₹5,271.9751 crore, while other national parties collectively received ₹1,783.9331 crore.

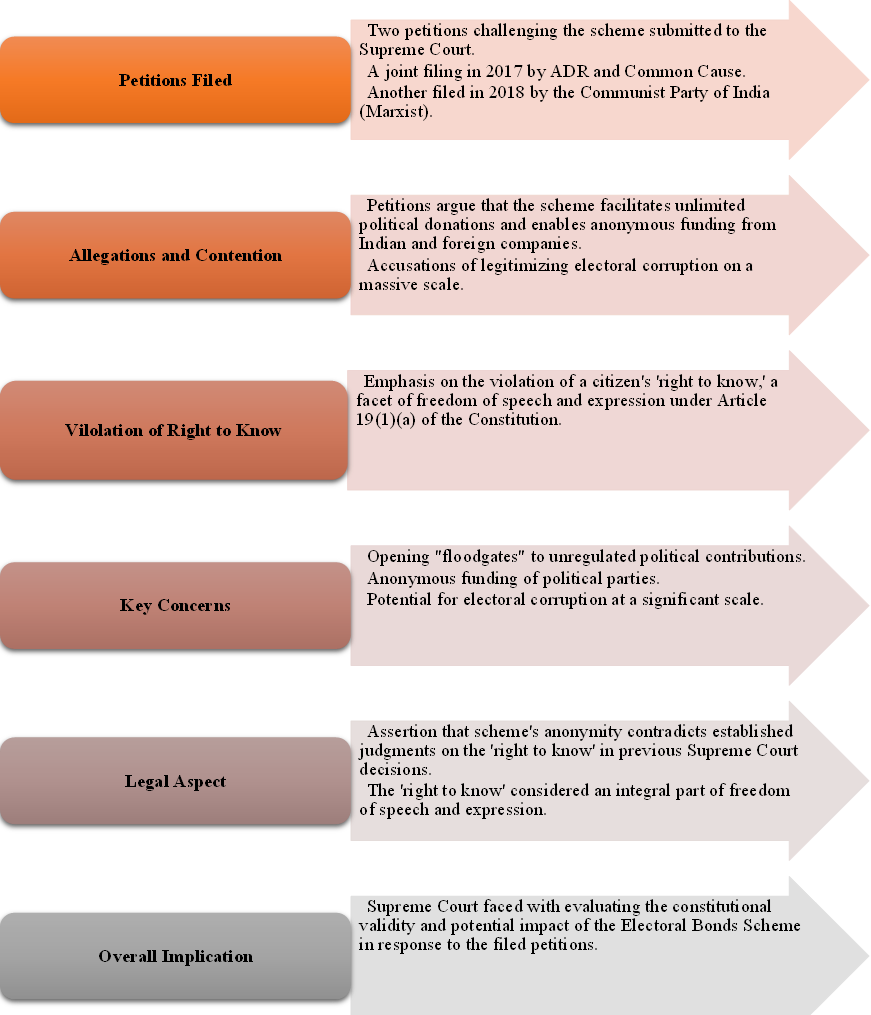

Why is the scheme facing a challenge in the Supreme Court?

Amendments to the Electoral Bond Scheme

Key takeaways on SC verdict on electoral bonds scheme

Violation of the Right to Information

- The scheme allowed anonymous political donations, violating the fundamental right to information under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution.

- The right to information extends beyond freedom of speech, playing a crucial role in enhancing participatory democracy and government accountability.

Not Proportionally Justified to Curb Black Money

- The government did not adopt the least restrictive methods to achieve its objective, as emphasized in the KS Puttaswamy case on the right to privacy.

- Examples of least restrictive methods include the ₹20,000 cap on anonymous donations and the concept of Electoral Trusts.

Right to Donor Privacy Does Not Extend to Contributions Made

- Financial contributions to political parties, often made for support or quid pro quo, should not be treated uniformly for all contributors.

- The right to privacy of political affiliation does not extend to contributions made to influence policies, reserved for genuine political support.

Unlimited Corporate Donations Violate Free and Fair Elections

- Amendment to Section 182 of the Companies Act, 2013, allowing unlimited political contributions by companies, deemed manifestly arbitrary.

- Changes removed the cap on company donations and eliminated the disclosure requirement in Profit and Loss accounts.

Amendment to Section 29C of RPA, 1951 Quashed

- The Finance Act, 2017, amended Section 29C of the Representation of the People Act, 1951, creating an exception for donations through electoral bonds.

- Striking down the amendment, the court found the original requirement to disclose contributions above ₹20,000 to balance voters’ right to information with donor privacy.

Concerns Raised by the ECI

- In 2019, the ECI filed an affidavit in the Supreme Court expressing concerns about electoral bonds.

- It warned that the scheme could undermine transparency in political funding and invite foreign corporate influence.

- Amendments could lead to the creation of shell companies for making political donations, rendering ECI guidelines redundant.

ECI’s Caution and Opposition

- The ECI cautioned against amendments in May 2017, emphasizing the importance of declaring donations for transparency.

- It opposed the RP Act amendment allowing parties to skip recording donations through electoral bonds, terming it retrograde.

- The ECI urged the Ministry to permit political donations only from profitable companies with a proven track record.

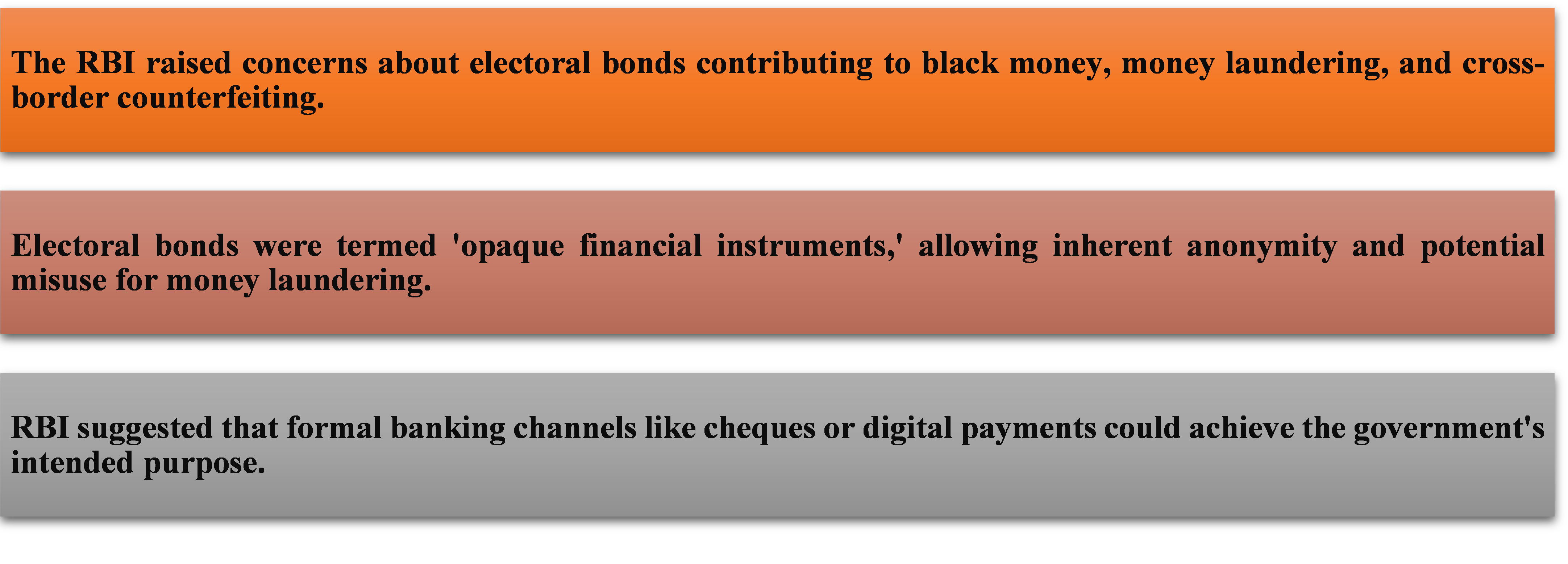

RBI Objections

Government’s Defense of the Scheme

- The government emphasized that electoral bonds promote transparency in political funding.

- Bonds can only be encashed by eligible political parties through authorized banks, ensuring anonymity.

- The scheme is deemed transparent, preventing the funneling of black money, according to the Solicitor General.

Supreme Court’s Earlier Actions

- Before the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, the Supreme Court refused to stay the scheme, recognizing its weighty impact on the electoral process.

- An interim order directed political parties to provide information on donors and contributions through electoral bonds to the ECI.

- In March 2021, the Court declined to stay the sale of bonds, stating safeguards had been provided in earlier orders.

Recent Supreme Court Proceedings

- In January, the Court divided petitions into three sets, addressing challenges to the scheme, RTI applicability to political parties, and amendments in the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act.

- In March, petitioners requested the matter to be referred to a Constitution Bench for an authoritative pronouncement due to its impact on democratic polity and party funding.

MPSC राज्य सेवा – 2025

MPSC राज्य सेवा – 2025