Relevance to the UPSC

For UPSC Prelims, topics like the Citizenship Amendment Act, Citizenship Act of 1955, methods of acquiring citizenship in India, the Foreigners Act of 1946, Sixth Schedule, Inner Line Permit, National Register of Citizens, and the Assam Accord are crucial for understanding India’s legal framework on citizenship and migration. These topics are directly relevant to the Indian Polity and Governance segment, testing knowledge of constitutional provisions, policy, and legal mechanisms. For Mains, a deep dive into the “Concerns Related to the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019” requires analytical skills to evaluate its social, political, and constitutional implications, essential for General Studies II, focusing on governance, social justice, and polity.

Why in the news?

Recently, after more than four years since its passage by the Indian Parliament in December 2019, the Indian government has officially notified the rules for the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019. This significant development marks the operational beginning of the Act, which aims to offer a streamlined pathway to Indian citizenship for migrants from six specified religious minorities: Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis, and Christians, originating from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan. The notification of these rules is a crucial step in the implementation process of the CAA, indicating the government’s move forward with its enactment and application.

What is Citizenship?

Citizenship is a legal status and relationship between an individual and a country that includes specific rights and responsibilities. It means being a member of a country, with certain values and the right to take part in political life. People become citizens through a country’s legal process and, as citizens, can enjoy certain benefits like voting and owning property. In return, they must follow the country’s laws and defend it if needed. However, citizenship also means more than just legal status; it’s about feeling connected, having a sense of belonging, and sharing cultural values.

Not everyone living in a country is a citizen. For example, people from one country living in another are considered foreigners, or “aliens,” and their rights are based on international agreements and the host country’s laws. While in the U.S., these individuals must follow laws, pay taxes, and enjoy some protections and rights like owning property and doing business. Yet, they can’t vote or hold public office until they become citizens. This distinction highlights the difference between simply residing in a country and being a full citizen with all associated rights and duties.

Historical evolution of citizenship – From an elite club to an inclusive democracy

Citizenship started way back in Ancient Greece, where it was a special role for some people, allowing them to help decide how their city-state was run. But not everyone could be a citizen—many were left out, like women, slaves, and foreigners. Being a citizen back then wasn’t just about having rights; it was also about doing your part for the community. Aristotle, a famous thinker, said that a good citizen needs to know how to follow rules and how to help make them.

For a long time, in places like Ancient Greece, being a citizen was a mix of being part of an exclusive club and having responsibilities. The idea of democracy they had wasn’t full and fair by today’s standards—it took a lot of struggles and changes over centuries to get closer to the democracy we know today.

As time went on, especially around the 1600s and with events like the French Revolution, the idea of who could be a citizen began to change. The French Revolution made a big statement that everyone should have a chance to be involved in making decisions, not just the rich or powerful.

The Enlightenment, a time when people started thinking differently about freedom and individual rights, pushed these ideas even further. Citizenship began to mean having a set of rights and duties within a country, like voting or following the law.

In the 1800s, owning land was a big part of being a citizen, but this started to change. By the 1900s, more people, including workers, demanded to have rights too, making citizenship something that everyone born in or moving to a country could have.

Over time, as the world changed with big events like wars and countries becoming independent, the idea of citizenship kept evolving. Now, with people moving around the globe more than ever, there are many ways to become a citizen, sometimes even of two countries.

This story shows us how the idea of being a citizen—having rights and responsibilities in your country—has grown and changed through history, making it something we can all be part of today.

What are the Different types of citizenship?

- Family Citizenship (Jus Sanguinis): Citizenship by descent, allowing individuals to inherit nationality from family members.

- Citizenship by Birth (Jus Soli): Automatically grants citizenship to individuals born within a country’s territory.

- Citizenship by Marriage (Jus Matrimonii): Offers a pathway to citizenship through marriage to a national of the country.

- Naturalization: A process for non-citizens to acquire citizenship after meeting specific criteria.

- Economic Citizenship: Enables citizenship through significant financial investments in the country’s economy.

- Temporary Citizenship: Provides legal status to vulnerable groups like refugees for a limited time.

- Dual Citizenship: Allows individuals to hold citizenship in two different countries simultaneously.

- Quasi-Citizenship: Offers former nationals residing abroad certain rights akin to citizenship status.

Scholars differentiate between two types of citizenship based on how people become members of a community. Civic citizenship is about following a country’s laws and is open to anyone who meets these legal requirements. Ethnic citizenship depends on a person’s ancestry or ethnicity. For example, countries like the Swiss Federation and the USA focus on civic citizenship, meaning laws and principles guide citizenship. On the other hand, countries like Germany, Japan, and Israel consider ethnic background as a key factor for citizenship.\

The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019: An In-depth Look

The Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019, represents a significant amendment to the Citizenship Act of 1955, introducing provisions for granting Indian citizenship to specific religious minorities from three neighboring countries. This legislative move has been both applauded and criticized, sparking debates across the societal and political spectrum of India.

Delighted that the Lok Sabha has passed the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2019 after a rich and extensive debate. I thank the various MPs and parties that supported the Bill. This Bill is in line with India’s centuries old ethos of assimilation and belief in humanitarian values.

— Narendra Modi (@narendramodi) December 9, 2019

Objective of the CAA

The primary objective of the CAA is to provide a streamlined path to Indian citizenship for persecuted religious minorities from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan. It specifically addresses the needs of Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis, and Christians who fled to India to escape religious persecution in their home countries, underlining India’s commitment to protecting those vulnerable to such injustices.

Key Provisions of the CAA

Eligibility Criteria

The Act sets forth criteria for eligibility:

- Migrants must belong to one of the six specified religious minorities.

- They should have originated from Pakistan, Bangladesh, or Afghanistan.

- Their arrival in India should be on or before December 31, 2014, to be considered under this Act.

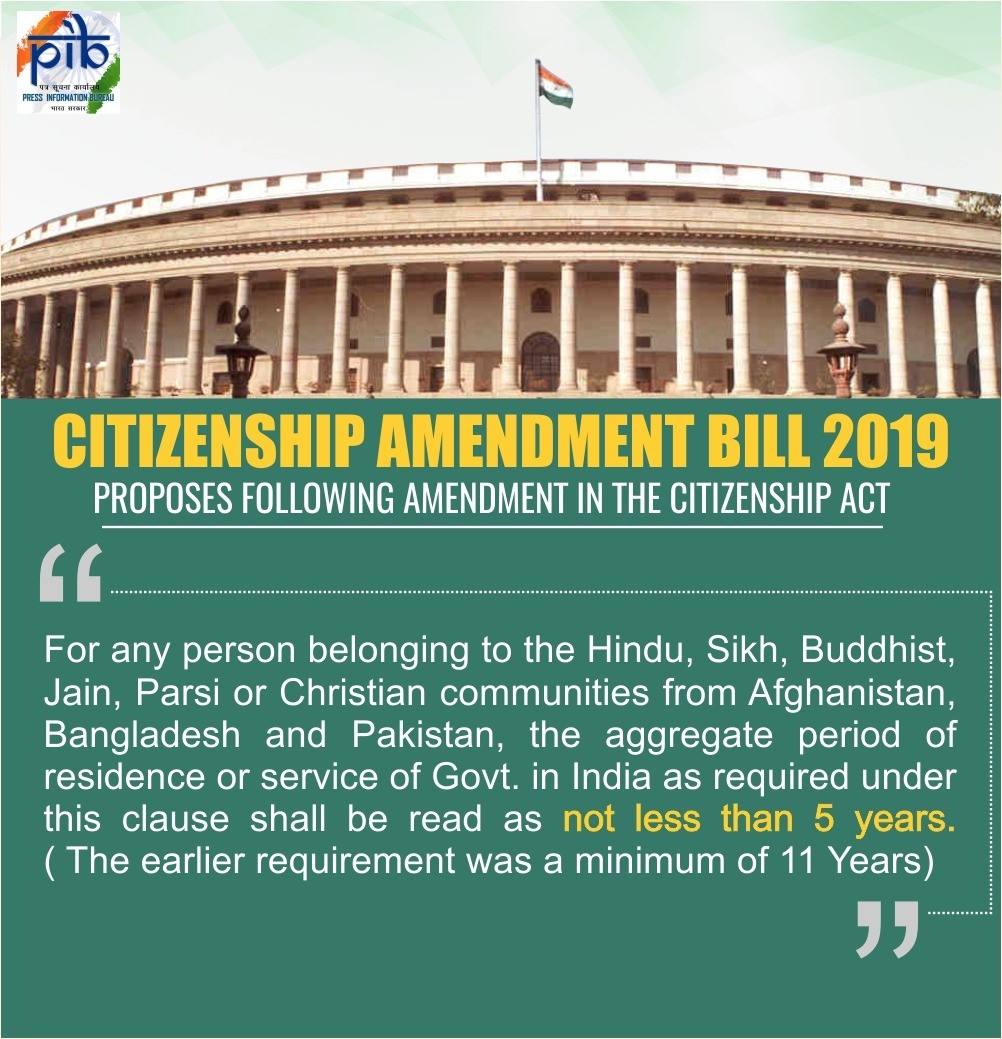

- Simplification of Naturalization Process

- One of the hallmark provisions of the CAA is the relaxation of the naturalization process for eligible migrants. Traditionally, the Citizenship Act, of 1955, requires an individual to have resided in India for 11 of the preceding 14 years to apply for citizenship by naturalization. The CAA reduces this requirement to 5 years for the specified groups, facilitating a quicker path to citizenship.

Documentation and Application Process

- Applicants under the CAA need to provide evidence of their eligibility, including proof of religion, country of origin, and date of entry into India. The legislation allows for a range of documents to be used for this purpose, catering to the challenges many refugees may face in obtaining formal paperwork.

Administrative Mechanisms

- The implementation of the CAA involves several administrative mechanisms:

- The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) is the primary body overseeing the application and verification process.

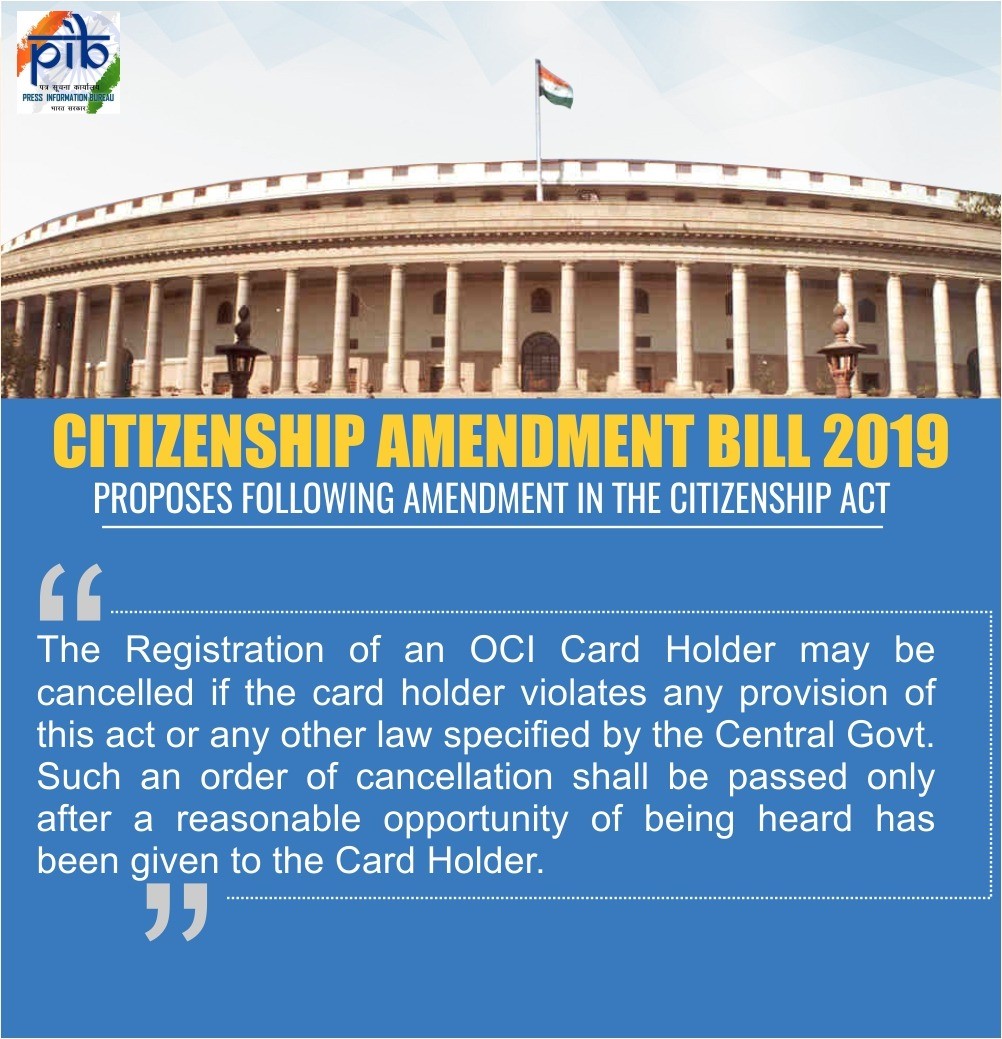

- Applications are processed through a system involving background checks by security agencies and reviews by committees specifically established for this purpose.

- Empowered committees, consisting of officials from various departments, are tasked with making final decisions on citizenship applications under the CAA.

Exemptions and Clarifications

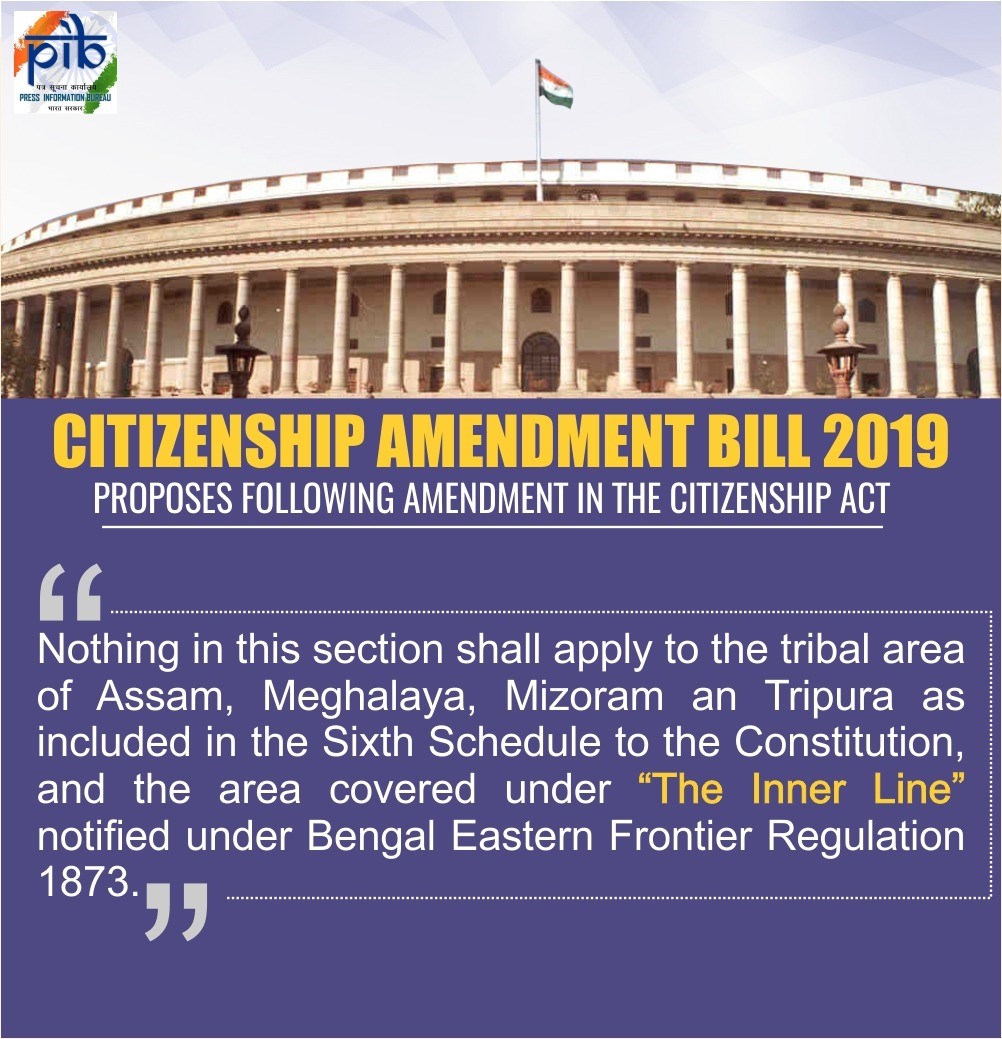

- The CAA explicitly exempts certain regions from its purview, including areas covered by the Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution and those under the Inner Line Permit (ILP) regime. This move aims to address concerns related to the demographic and cultural impact on indigenous communities in the northeastern states of India.

In Conclusion

- The Citizenship Amendment Act, of 2019, carves out a specialized pathway for citizenship for specific religious minorities from neighboring countries, reflecting India’s stance on providing refuge to those fleeing religious persecution. By simplifying the naturalization process and specifying clear criteria for eligibility, the CAA aims to expedite the inclusion of these vulnerable groups into the Indian polity. However, the Act’s implementation and the broader implications continue to be a subject of intense debate and discussion, highlighting the complex interplay between national security, human rights, and India’s secular ethos.

Points of Contention

Constitutional and Secular Principles

- A major criticism of the CAA centers on its perceived deviation from the secular principles enshrined in the Indian Constitution, specifically Article 14, which mandates equality before the law regardless of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth. Critics argue that by delineating eligibility for citizenship based on religious affiliation, the CAA introduces a discriminatory criterion that could erode the secular foundation of the Indian state.

Disenfranchisement Concerns

- The potential linkage of the CAA with the National Register of Citizens (NRC), intended to identify illegal immigrants, stokes fears of disenfranchisement for individuals unable to produce the required documentation. The experience from Assam’s NRC, where over 19 million people were left out, amplifies these apprehensions, suggesting that a nationwide NRC could exacerbate the risk of statelessness among India’s poor and marginalized, who often lack formal documentation.

Regional Implications and Social Harmony

In Assam and other northeastern states, concerns about the CAA disrupting local demographics and violating the Assam Accord, which sets 1971 as the cut-off year for recognizing immigrants, highlight regional apprehensions. Moreover, the exclusion of Muslim immigrants from the act’s provisions has ignited debates over its impact on India’s communal harmony, with critics arguing that it could foster division and marginalize Muslim communities further.

Government’s Arguments in Support

Humanitarian Considerations

- The Government defends the CAA as a humanitarian gesture aimed at providing refuge to persecuted minorities from the neighboring Islamic states of Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan. It underscores the act’s intention to offer a dignified existence to those who have historically faced religious persecution, aligning with India’s long-standing tradition of sheltering the oppressed.

No Impact on Indian Citizens

- A key point in the government’s defense is the assertion that the CAA does not affect the citizenship status of any existing Indian citizen, irrespective of their religion. The government emphasizes that the act is exclusively designed to aid non-citizen refugees and should not be misconstrued as a tool for stripping any Indian of their citizenship rights.

Exemptions and Safeguards

- Addressing concerns about the act’s potential impact on the northeastern states, the government points to the exemptions provided for regions under the Sixth Schedule and the Inner Line Permit (ILP) system. These exemptions aim to protect the indigenous cultures and demographics of these areas, demonstrating the government’s responsiveness to regional sensitivities.

Legal and Constitutional Validity

- The government also asserts that the CAA is legally sound and constitutionally valid, arguing that providing citizenship based on reasonable classification, such as persecution risk, is within the purview of the state’s powers. It contends that the act does not contradict the principles of equality as it is tailored to address the specific needs of a vulnerable group facing unique challenges.

Way Forward

Comprehensive Refugee Policy

- India must formulate a comprehensive refugee policy that aligns with international norms, such as those outlined by the UN Refugee Convention. This policy should prioritize non-discrimination on grounds of religion or ethnicity and embrace the principles of equality and human dignity.

Documentation Support

- The government must proactively assist individuals, particularly those from marginalized groups, in acquiring necessary documentation. This initiative is crucial to prevent the risk of statelessness and ensure that all citizens have the means to prove their citizenship.

Inclusive Dialogue

- The government must engage in open and inclusive dialogue with all stakeholders, including civil society organizations, religious groups, and communities affected by the CAA. Such dialogue can foster understanding, address concerns, and facilitate the implementation of the act in a manner that respects India’s diverse social fabric.

Awareness and Education

- There should be a concerted effort to raise public awareness and understanding of the CAA through factual, unbiased information campaigns. Educating the populace about the objectives, implications, and processes of the act can dispel myths and build an informed consensus on its execution.

Important Q’s in the news?

Conclusion

The Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019, has emerged as a focal point of debate, reflecting the intricate balance India seeks between offering sanctuary to persecuted minorities and preserving its secular ethos. The act’s humanitarian goals, set against concerns regarding its potential impact on India’s constitutional and social harmony, underscore the need for a nuanced approach to its implementation.

As India navigates these challenges, the path forward lies in ensuring that the principles of inclusivity, transparency, and dialogue guide the act’s execution. By fostering a comprehensive understanding of the CAA, supporting those in need of documentation, and engaging with the concerns of all communities, India can uphold its commitment to human dignity, equality, and the protection of the vulnerable. This balanced approach will not only affirm India’s stature as a diverse, democratic polity but also reinforce its legacy as a refuge for those seeking sanctuary from persecution.

Network state – New concept of nation state and digital citizenship

Imagine a new kind of country that exists online, where people from all over the world come together not because they share the same land, but because they share the same ideas and goals. This is the idea behind the “Network State,” a concept introduced by Balaji Srinivasan. Unlike traditional countries that are tied to a specific location, Network States are formed on the internet, connecting people across the globe.

Here’s how it works: a Network State starts as a community online where people agree on certain values and objectives, like fairness, justice, or improving health. Through the power of the internet, this community can act together, even raising money to buy land anywhere in the world. Over time, these Network States could become recognized by traditional countries, making them a new kind of nation.

But not just any online group can become a Network State. It has to be more than just a social network like Facebook or a digital currency like Bitcoin. A Network State needs to aim for diplomatic recognition, setting it apart as a serious endeavor to create a better society.

Think of a Network State as not just a place on a map, but a space in our minds and digital lives. It’s an exciting idea that turns political science into something more active and creative, almost like “political technology.” It’s about using technology not just to start new businesses or social networks, but to rethink what a country can be in the digital age.

UPSC GS Foundation Prelims+Mains for 2026

UPSC GS Foundation Prelims+Mains for 2026